Exactly when builders in Yemen began to use alabaster windows is not known.

But the tradition was clearly established by the time the rulers of the ancient Yemeni state of Sheba (or Saba) began building Ghumdan, their sumptuous skyscraper palace in Sana'a, 1,800 years ago. The poet al-Hamdani later described it

Rising, soaring into the midst of the sky,

Twenty floors of no mean height,

Wound with a turban of white cloud

And girdled with alabaster.

The palace's most famous feature was a belvedere on its summit, roofed with a single panel of flawless alabaster. This was said to be so translucent that you could tell crows from kites as they flew overhead. Not to be outdone, the Ethiopians who conquered Yemen in the sixth century included a panel of alabaster 5m square in the dome of their cathedral.

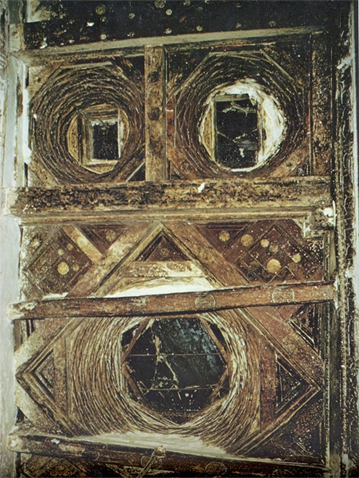

The remains of these great buildings now lie, unexcavated, beneath the later city. The earliest alabaster visible in situ is less than a stone's throw from the site of Ghumdan – several panes, now blackened with time and plastered over from the outside, let into the ceiling of the Great Mosque. They originally illuminated the area of the main prayer-niche of the mosque, and probably date from a reconstruction of the building in the early eighth century.

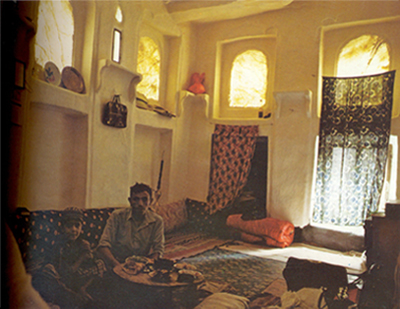

Alabaster was not limited to palaces and mosques. Al-Hamdani wrote of the typical houses of Sana'a in the early tenth century: 'The alabaster panes transmit the sun's brightness to the plastered interior, which reflects its essence and its brilliance.' Alabaster was also set into the domes of bath houses, and another poet described bathing under 'a sky with many moons'. While window glass was still a luxury in Europe, Yemenis had found an answer to the problem of illumination – under the ground.

The tradition continued. But in the 1950s and 1960s, as Yemen began to open up to the international economy, the price of imports from abroad began to fall. The labour-intensive industry of alabaster cutting was unable to compete, and the alabaster windows of Yemen were eclipsed by cheap imported glass.

It seemed that the houses of Sana'a would never again be lit by qamari, that mysterious moonlight from beneath the ground. And then, in the 1990s, Abdulwahhab al-Sayrafi – whose family had been the most famous alabaster cutters in Yemen for as long as anyone could remember – began to revive the ancient and illuminating heritage of Sheba's architects.

Alabaster cutter in Sana'a , 1937 .